The Filipino is worth dying for.

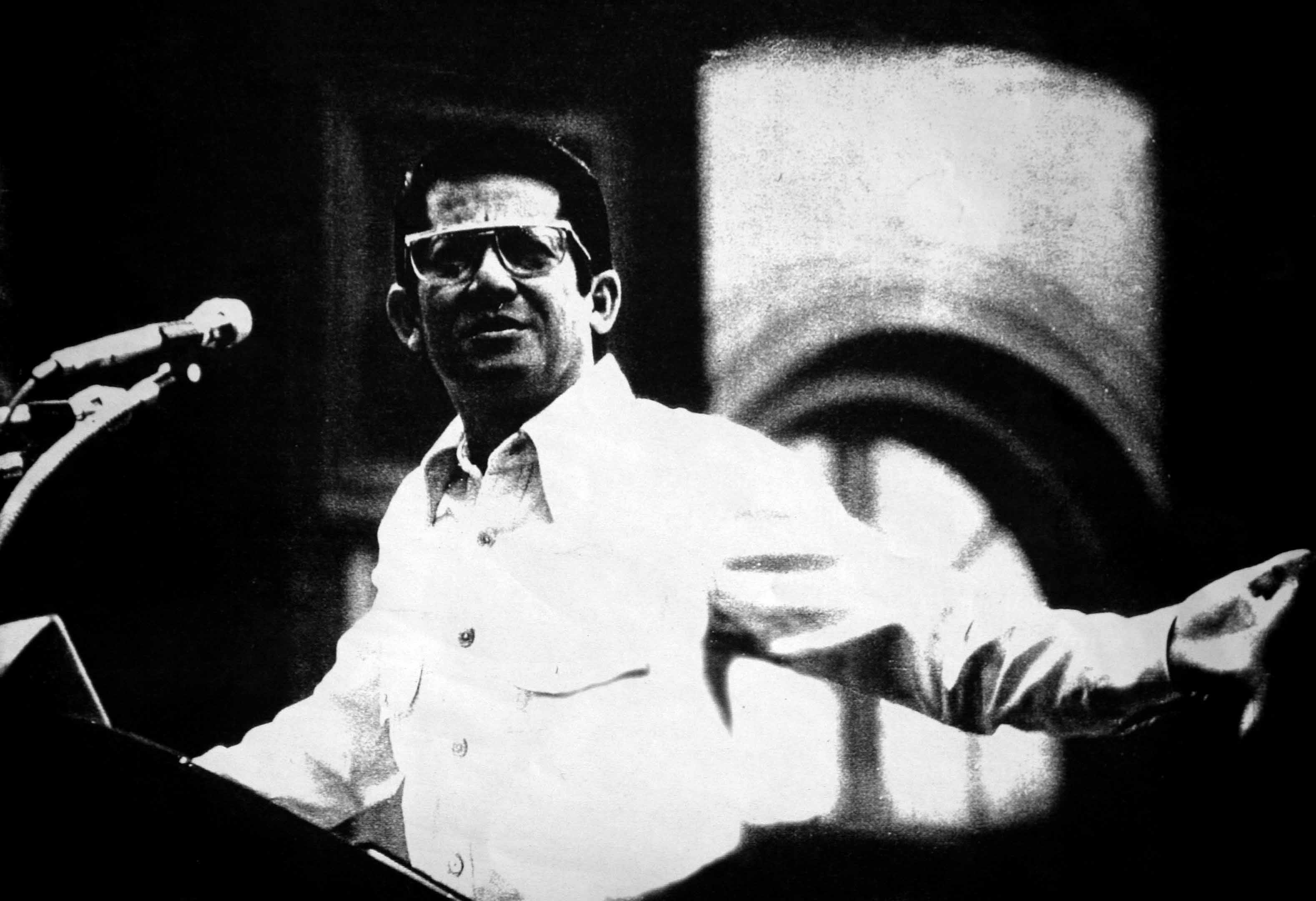

Benigno Simeon "Ninoy" Aquino, Jr. (November 27, 1932 – August 21, 1983) was the husband of Philippine President Corazon Aquino. Aquino, together with Gerry Roxas and Jovito Salonga, formed the leadership of the opposition towards Ferdinand Marcos. Shortly after the imposition of martial law, he was arrested in 1972 along with other dissidents and incarcerated for seven years. In 1980 Aquino was permitted to travel to the United States for medical treatment following a heart attack. He was assassinated at the Manila International Airport in 1983 upon returning from his self-imposed exile. His death catapulted his widow, Corazon, into the political limelight, and prompted her to run for president as member of the UNIDO party in the 1986 snap elections.

Key events from Ninoy's life

He left Logan International Airport on August 13, 1983, took a circuitous route home from Boston, via Los Angeles to Singapore. He then left for Hong Kong and on to Taipei. From Taipei he flew to Manila on then Taiwan's flag carrier China Airlines Flight 811.

Aquino was assassinated on August 21, 1983, when he was shot in the head after returning to the country. At the time, bodyguards were assigned to him by the Marcos government.